罷工!香港勞工鬥爭追憶錄

Source: 明報Ming Pao Daily

罷工!香港勞工鬥爭追憶錄

城市大學Chris Chan 陳敬慈教授為本報闡述香港各大工會的往史,藉以借古鑑今,了解工會立場關係的種種由來,從而展望勞工運動的下一個里程碑。

在 本年五月六日,貨櫃碼頭工潮終於告一段落,並在香港的社會勞工抗爭事件簿中寫下重要的一頁。一來因為工潮歷時整整四十天,在香港實屬前所未聞;二來公眾和 學界就外判工人薪酬待遇的一連串廣泛討論及參與支持都反映了工潮所帶來的深遠意義。再者,社會事後亦對勞工在缺乏集體談判權下孤掌難鳴的窘局有更深了解。

是次工潮的動員力以及物資協調力都相當可觀,來自民間的空前支持亦延伸至學界、私營政治組織乃至社會各階層的市民。透過碼頭工 人及其支持者的努力不懈,為全體勞工爭取權益再非天方夜譚。以史為鏡,回首昔日的勞工抗爭,尤其是勞工團體及非政府組織於其中的作用,能有助深入分析工潮 在今後的重要性。

六七暴動前話

香港在英治時期主要擔任著轉口港的角色。但在上世紀四五十年代,大量資金隨著內地難民流入香港,令本地工業在整個五十年代蓬勃 發展。香港市場結構亦因而從純轉口港轉變為手工業主導的經濟模式,當中以紡織及服裝業尤為重要。這些早期的工廠大多屬小規模經營,而廠工在分散的僱用模式 下亦難以組織起來。此外,由於內地難民不斷湧入,導致勞動力供應過盛,故員工薪金並沒有因經濟繁榮及工業化起飛而得到增加。

談及勞工法例,港英政府一直奉行自由放任主義政策,對員工及社會保障關注甚微。政府更於一九四九年立法限制公營勞工不能在未與資方協商的情況下舉行罷工,並一併禁止跨行業罷工。

即便如此,左右兩派的工會已在一年前組成各自的聯盟,以作為對於同年成立的香港僱主聯合會的反擊。在該年四月,三十一個親中國共產黨的工會組成了香港工會聯合會(工聯會);而港九工團聯合總會(工團總會)則由親國民黨陣營的工會組成。

四十年代後期的工會運動有著頗為濃厚的鬥爭色彩。在一九四八及一九四九年,由於工資增長落後於通漲,大型罷工不時發生。

然而,由於中英關係在五十年代有所改善,左派工會的抗爭行為亦變得較為收儉。與這些工會對立的右派工會則向僱主示好以作回應。

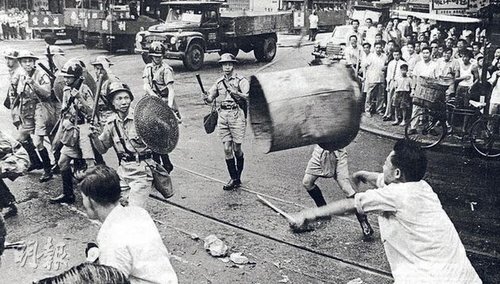

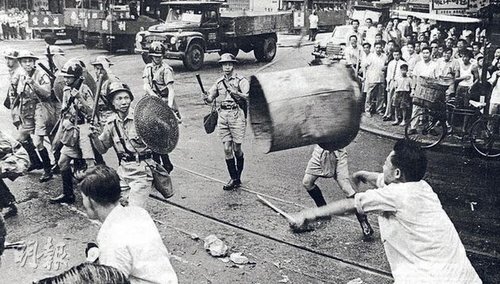

六七暴動及其影響

六七暴動乃是香港勞工運動的一個分水嶺。多重原因激發了在一九六七及一九六八年間的數次暴動,當中包括高通漲導致的貧富懸殊、港澳兩地居民的反英反葡情緒、以及中國大陸文化大革命所帶來的影響。這些因素都促成了左派份子策動反殖民運動。

暴動始於六七年夏天終於六八年冬天。在六七年四月,一間位於新蒲崗的人造花廠由於資方減低員工薪酬權益而引發勞資糾紛,成為暴 動的導火線。紛爭升級令工聯會成立港九各界同胞反對港英迫害鬥爭委員會(鬥委會),旨在打倒殖民政府。鬥委會數次的大罷工號召都以失敗收場。同年七月,暴 力抗爭正值白熱化,警方突擊搜捕左派份子,而左派份子則以炸彈遍佈全港,襲擊警察及政府場所作為還擊。

暴動過後,港英政府著手透過改革安撫緩和社會的不安不滿。當中包括訂立新勞工法、推廣公務員工會及成立公營勞工咨詢機制。這些改革都給予了民間勞工運動一個絕佳的發展良機。

勞工階層固然獲得殖民政府讓步,但工聯會因其暴力抗爭手法而遭政府及主流媒體邊緣化。相反,工團總會的部份領袖卻被政府招攬至轄下咨詢機構。兩者都在事件中失去民心,新的民間工會便於七十年代應運而生。

七十至八十年代:本土勞工運動冒起

六七暴動改變了勞工運動發展的全貌。在七十年代,勞工行動及組織百花齊放成為了主流現象。

在這段時期,工聯會和工團總會這兩個政治理念掛帥的工會都失去了代表性。前者成為了服務提供者,但對勞資糾紛近乎不聞不問。失 意的勞工們唯有自救並尋求其他組織協助,曾在兩大聯會舉足輕重的公司成員,如中電(CLP)及大東紡織廠(Tai Tung Textile Factory)等都選擇繞過工會自行了斷。這些事件說明了兩大陣營的運作模式及理念都已無法代表勞工階層並維護他們的權益。

帶有宗教背景的勞工團體,如香港基督教工業委員會(工委會)等開始肩負起為員工爭取權益及工會教育的職責。此期間,民間勞工運 動將精力集中於倡導立法保障員工安全、與社會運動接軌及涵蓋更多社會民生問題上。政治理念問題在最初並非民間工會的考慮要素。然而,隨著八十年代中英雙方 就香港於一九九七年後的歸屬問題展開談判,這些工會已無力抵抗政治旋渦,更遑論置之度外。

當港英政府就立法改革進行咨詢時,工委會聯同一眾草根工會提出立法局直選並廢除所有委任議席。這些工會追求民主發展,而北京當 局則強調穩定繁榮。與時同時,工委會與捲土重來的工聯會之間的分歧亦日漸加深。工聯會掌控了勞工界的代表議席,並阻止當時的工委會理事劉千石加入於一九八 五年成立的基本法咨詢委員會。由於劉鼓吹一九八八年立法局直選並聯同積極分子至北京抗議,其回鄉證及後遭到沒收,失去了入境中國大陸的權利。

在一九八九年天安門廣場示威中,工委會與學生及北京工人自治聯合會站於同一陣線。當時的工委員成員李卓人在攜帶物資給留守學生時遭北京當局扣押。這一連串的事故在民間工會中激起了結合起來以應對社會問題的迫切需要,尤其要為九七年的變局作好準備。

自主工會聯合組織 – 香港職工會聯盟

獨立工會組織香港職工會聯盟(職工盟)於八九北京學生民主運動後成立。成千上萬的勞工呼應獨立工會的動員號召,上街支持學運。 工委會理事,其後成為職工盟創會主席的劉千石以及工委會組織人,其後成為職工盟秘書長的李卓人成為了反對派領袖中的耀眼之星。職工盟於一九九零年七月正式 成立,創會時有二十五個屬會及六萬五千名會員。為闡明堅定立場,職工盟以「團結」、「飯碗」、「公義」、「民主」為其爭取目標。此前,部份與工委會協作的 工會曾於一九八四年另立港九勞工社團聯會,但該會從九零年起已成為職工盟屬下的一員。職工盟因其長期爭取民主的形象而於眾多工會中別樹一幟。作為一個非政 府組織,工聯會的運作及組織文化都相近於其他非政府組織,它們亦一直合作無間。此外,工聯會亦是國際主義的忠實支持者。

自成立起,工聯會一直致力於協助組織勞工,主要手段為介入勞資糾紛(貨櫃碼頭工潮即為一例)、勞工培訓及教育、參選及參與議會政治、代表勞工就立法發聲、鼓吹落實政策等等。

工聯會一直為保障勞工權益提出動議案及修正案,主要針對歧視工會個案及集體談判權。對於前者,曾提出的議案多數包括防止工會成員遭到不公平革職,以及保障他們在勝訴後能得到相應賠償和復職。

就後者立法乃由職工盟首開先河。它令僱主必須認可擁有至少四分之一公司成員的工會及其草擬集體談判協議的權利。自從職工盟秘書長李卓人在一九九五年當選立法局議員伊始,他就一直致力讓集體談判權議案得以通過。

議案在一九九七年六月載入勞工條例,但在七月十七日,亦即主權交接後,臨時立法會將其連同另外六條勞工條例一併暫延,更於十月 二十九日在《一九九七年僱傭及勞資關係(雜項修訂)條例》中遭廢除 – 當時公眾並沒有太大迴響。當職工盟強烈抗議的同時,工聯會成員卻投下了棄權票。

九七回歸後,工聯會、工團總會及職工盟都各自踏上不同的道路。工聯會採取了親政府立場;工團總會在缺乏國民黨的支持下每況愈 下;職工盟則壯大成有著鬥爭色彩的第二大工會。現今,職工盟已有八十八個屬會及十七萬名成員,而工聯會則有一百八十一個屬會及三十四萬一千名成員。研究香 港勞工歷史的著名學者陳明銶教授曾提到:「職工盟聯同其社運盟友及親民主政黨在過去十年間結合成一股強大的力量,並與工聯會就民主化及勞工權益問題上形成 了楚漢相爭的局面。」

溫故知新

透過回首五十年代至今勞工運動的發展,人們能一窺各工會處理各種矛盾關係的手法,譬如在勞工動員、鬥爭及為其提供服務之間尋求平衡,在保持政治獨立及追求政府眼中破壞社會穩定的民主之間有所權宜,以及在自身僅作為工會團體還是定性為政治力量的身份認定上謹慎抉擇。

早前的碼頭工潮說明了爭取勞工權益在取得重大成果的背後,既需經過艱苦抗爭亦要面對無盡危機。這些抗爭與危機都會隨著「社運模式」的廣泛動員而來。

香港勞工運動在近期取得了如立法落實最低工資等等的重大里程碑。若職工盟及其社運盟友能如是次碼頭工潮中般表現出不懈的動員力,復立片刻風光的集體談判權的一天終會到來。

原文由陳敬慈教授以英文撰寫,由港報實習生霍潤文翻譯。

SEPTEMBER 16, 2013

資料來源:http://harbourtimes.com/openpublish/zh-hant/node/807

Strike! A Reminder of Past Labour Militancy in Hong Kong

Professor Chris Chan 陳敬慈examines Hong Kong’s union past to give context to the modern players, where they came from and from whence ancient animosities sprang. He finishes with a look to their aims for the future.

The Hong Kong dock workers strike ended on May 6, 2013. It was one of the most significant labour struggles in Hong Kong’s recent social history. Not only did it last for a record-setting long time – 40 days – but it roused notable support of public and students on a labour issue, and made the wages and working conditions of subcontracted workers a matter of widespread social debate. It also exposed the harm to workers and difficulty of gaining improvements in their work conditions and pay when lacking collective bargaining rights.

The extended strike, been carried out with great mobilization and coordination of collected resources, reflected in part the unprecedented level of support from students as well as the general public and other self-organized political groups. The strike has made it seem more possible to gain labour rights for all, through the courage and persistence of the workers and their supporters.

To understand the significance of this strike now, and in the future, it is necessary to be aware the history of past labour struggles in Hong Kong, especially of the roles of key organizations: the labour federations and NGOs.

Before 1967

Under British rule, Hong Kong mainly played the role of a trading entrepot. However, the capital brought by the Chinese refugees who escaped from Communist China in the late 1940s and early 1950s helped Hong Kong industry to develop throughout the 1950s. This also caused a structural change in Hong Kong’s economy from a purely trading entrepot to a manufacturing-oriented economy, mainly reliant on the textile and garment industry. These enterprises were often small in size. This scattered employment pattern made organizing labour difficult. The prosperity and rapid industrialization did not lead to higher wages, as the endless arrivals of Chinese refugees kept wages at a very low level.

In terms of labour policy, the British Hong Kong Government adopted the laissez-faire principle, with minimal labour and social protection. In 1949, a regulation against strikes in the public sector was passed to ban strikes unless the employees had gone through a mediation and arbitration process with the employers. It also banned cross-industry strikes.

Still, in 1948, both leftist and rightist trade unions built up their federations, as the workers’ response to the formation of the Employers’ Federation of Hong Kong, which had been established in the same year. In April 1948, 31 pro-Chinese Communist party trade unions formed the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (hereafter: HKFTU). The Hong Kong and Kowloon Trades Union Council (hereafter: HKTUC) was founded by the pro-Kuomintang camp.

The trade unions in the late 1940s operated rather militantly. Large-scale strikes took place in 1948 and 1949 when wages fell behind the pace of inflation.

As the diplomatic relations between China and Britain improved throughout the 1950s, however, the leftist unions became less confrontational with the employers. Seeing the leftists as competitors, the rightist unions tended to get closer to the employers as a response.

The 1967 riots and their impacts on labour movement in Hong Kong

The 1967 riots were a watershed in the labour movement of Hong Kong. There were various reasons behind the riots of 1967 to 1968, such as high inflation that widened the income gap; the anti-British sentiment of the people; the influence of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China; and the anti-Portuguese movement in Macau. All these played a role in inspiring the leftists to initiate an anti-colonialist movement in Hong Kong.

The riots lasted between the summer of 1967 and spring of 1968. The riots broke out in April 1967, when an artificial flower factory in San Po Kong cut the wages and benefits of its workers. The conflicts caused the FTU to form a Committee for Anti-Hong Kong British Persecution Struggle, with an objective of fighting against the colonialists. The committee attempted to organize general strikes, which ended in vain. In July, at the height of the violence, police raided and arrested the leftists. They retaliated by planting bombs throughout the city, targeting police and damaging government properties.

After the riots, the Hong Kong Government launched a series of reforms, to calm the people and dispel discontent. These included new labour regulations, union promotion among civil servants and the formation of a labour consultation mechanism in the public sector. These reforms offered a golden opportunity for the independent labour movement to spread.

Although workers got social concessions from the British colonial government, the HKFTU was marginalized by both Hong Kong government and mainstream media for its violence in the rebellions. As for the HKTUC, the British ruler absorbed its leaders into government consultation institutions. Both of the camps lost their popularity among workers, and new independent trade unions became established in 1970s.

1970-1980s: Local labour movement on the rise

The 1967 riots changed the course of labour movement completely. In the 1970s, more independent labour actions took place and more labour organizations came into existence.

During the post-riot 1970s, the two political ideology-charged labour federations, HKFTU and HKTUC, could no longer represent the working class. The HKFTU became a service-provider but kept quiet or even turned a blind eye to labour conflicts. Disappointed, workers became more self-reliant or sought help from other organizations to claim their rights. Workers in companies with long-established HKFTU and HKTUC affiliates also bypassed their unions and took actions by themselves, such as the workers at China Light & Power (CLP) and Tai Tung Textile Factory in 1970. These incidents signaled that the traditional organizing methods and ideologies of the two existing camps could no longer represent and protect workers’ interests.

Labour organizations with religious backgrounds, notably the Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee (HKCIC) also became a force for labour rights advocacy and trade union education. During this period, the main focuses of the independent labour movement were on pushing for better protection of labour legislations; to integrate the labour movement with social movement; and to cover a wider range of social and livelihood issues. At first the independent labour groups focused primarily on workers’ rights and interests and put aside political ideologies. In the 1980s, however, when the Sino-British negotiation on Hong Kong’s status after 1997 started, the labour movement could no longer ignore politics and stay uninvolved.

When the British Hong Kong government conducted a consultation about legislative reform, the HKCIC and other grassroots labour organizations proposed direct elections and the abolishment of the appointed seats in the Legislative Council. HKCIC and other independent labour organizations in the labour movement lobbied for democracy while the Beijing Government emphasized stability and prosperity. At the same time, the conflicts between HKCIC and HKFTU were also deepening. HKFTU dominated the labour sector representatives in the legislature and prevented Lau Chin-shek, the then HKCIC director, from becoming a member of the Basic Law Consultative Committee in 1985. Lau’s home return permit was confiscated, effectively denying him entry to China. His advocacy for direct elections for 1988 and his protests in Beijing with other social activists earned him this blacklisting.

During the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, HKCIC sided with the students and supported the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation. Its then staff member Lee Cheuk-yan brought donations from Hong Kong to support students in Beijing but was detained when he arrived. This series of incidents provoked a sense of emergency and solidarity among the independent trade unions and motivated them to build up a federation and to address social issues, especially in preparation for the eventuality of 1997.

Independent union federation HKCTU

The independent trade union centre, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU), was formed after the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement led by students in Beijing. Thousands of workers, mobilized by independent trade unions took to the streets to support the movement. Lau Chin Shek, the HKCIC director and later HKCTU Chairman, and Lee Cheuk Yan, the HKCIC organizer and later HKCTU General Secretary, became popular opposition political leaders. In August 1990, HKCTU was set up with 25 affiliates and 65,000 members. Distinguishing itself from its rivals, the new union federation laid down four basic principles: ‘Solidarity, Rice Bowl, Justice and Democracy.’ Before the formation of HKCTU, a group of trade unions working with HKCIC had established the Federation of Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions (FLU) in 1984, but since 1990, FLU has been an affiliate of HKCTU.

HKCTU has been unique among the union federations in its consistent call for democracy. It was founded as an NGO. Accordingly, its operations and culture are close to those of the NGOs and it has always operated in close partnership with the NGOs. It has also always been a supporter of internationalism.

From its establishment, it has carried out worker organizing – mainly through crisis intervention (such as on the recent occasion of the dock workers’ strike); worker training and education; election and parliamentary politics, representing workers’ needs in the legislature; and policy advocacy.

HKCTU has a number of proposals for revised or new legislation to provide increased protection and rights to workers; chief among them are those regarding trade union discrimination and collective bargaining. To stop trade union discrimination, proposed policies mainly focused on unfair dismissals of union members and their rights to claim compensation and reinstatement if the employer lost the case at court.

Collective bargaining rights were a new legislation raised by the HKCTU. It entitled unions that have 25% of the workforce as members to be recognized and to draft collective bargaining agreements with employers. After Lee Cheuk-Yan, the Secretary General of the HKCTU was elected as a LegCo member in 1995, he has actively advocated for a collective bargaining law.

The proposal was adopted into the Labour Ordinance in June 1997. However, it was suspended on 17 July 1997, together with six other labour ordinances, by the Provisional Legco that was established after the Handover. On 29 October 1997, it was abolished under the Employment and Labour Relations (Miscellaneous Amendments) Ordinance 1997 – with little outcry from the public at that time. While the HKCTU protested strongly at the time, the HKFTU’s members chose to abstain from voting.

After the handover of sovereignty in 1997, the three union centres went in different directions. HKFTU adopted a pro-government position. HKTUC lost significance with the rapid decline of its membership after the Kuomintang withdrew its support. HKCTU emerged as the second biggest union centre with a militant image. Up to now, the number of its affiliate unions rose to 88, with 170,000 members, while the HKFTU has up to 181 affiliations with 341,000 members. Ming K. Chan, a famous scholar on Hong Kong labour history, pointed out in his article that: ‘the CTU, with its social movement allies and the pro-democracy political parties, emerged during the past decade as a potent force into a new configuration of FTU vs. CTU, contending over democratisation and labour rights’.

Prospects for the future

Through a review of the development of the Hong Kong labour movement since the 1950s, we can see the pattern of tensions in unions between worker organization, militancy and provision of services; between political independence and calls for democracy which threaten the government’s concept of stability; and between identity as a workplace organization and a political force.

The recent dock workers’ strike has confirmed that significant gains for workers come at the cost of struggle and risk. This struggle and risk can be borne collectively through widespread, ‘social movement’-style mobilization.

The labour movement in Hong Kong has achieved important milestones recently, for example with the legislation of a statutory minimum hourly wage. If the HKCTU and allied social organizations succeed in mobilizing as diligently as in the dock workers’ strike, the day may come when the right to collective bargaining, so briefly enjoyed, is again restored to Hong Kong workers.

JUNE 14, 2013

Resource:http://harbourtimes.com/openpublish/article/strike-reminder-past-labour-militancy-hong-kong